| Bad Astronomy |

|

|

|

BA Blog

|

|

Q & BA

|

|

Bulletin Board

|

| Media |

|

|

|

Bitesize Astronomy

|

|

Bad Astro Store

|

|

Mad Science

|

|

Fun Stuff

|

| Site Info |

|

|

|

Links

|

| RELATED SITES |

| - Universe Today |

| - APOD |

| - The Nine Planets |

| - Mystery Investigators |

| - Slacker Astronomy |

| - Skepticality |

Buy My Stuff

Keep Bad Astronomy close to your heart, and help make me

filthy rich. Hey, it's either this or one of those really

irritating PayPal donation buttons here.

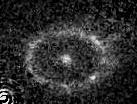

Supernova 1987A: The Inner Ring

Week of March 13, 2000

Last week I talked about what the outer layers of the precursor to SN87A were doing in the thousands of years before the explosion. Basically, they were being shed in two phases: a slow dense wind, which was shaped like a squashed sphere, and a fast lower density wind, which swept up the slower wind.

We knew something like this was going on before Hubble pointed its somewhat bleary eye towards 87A in 1990. Observations from another orbiting telescope made it pretty clear that there was something surrounding the star, though we didn't know what. That 'scope didn't take pictures, but instead was able to tell us that something around 87A was putting out lots of ultraviolet light. Scientists at the time knew that the light was coming from gas that was being lit up by the bright light of the new supernova, but the shape of the gas was not known. Everybody assumed a sphere, or maybe a slightly oblate sphere.

Boy, were they wrong! When we got the Hubble images, we were pretty

surprised to see a ring of

gas around the supernova. Even a simple analysis showed that it

really was a ring, and not some sort of odd sphere seen with a

bright rim around it (like a soap bubble, which looks brighter

around its edge). How the ring was formed was not hard to imagine.

As the fast wind expanded, it had a harder time pushing through the

thicker part of the slow wind, and piled up. You get a circle of

gas that way, and when tilted it looks like an ellipse, like

the rim of a drinking glass seen edge on.

Boy, were they wrong! When we got the Hubble images, we were pretty

surprised to see a ring of

gas around the supernova. Even a simple analysis showed that it

really was a ring, and not some sort of odd sphere seen with a

bright rim around it (like a soap bubble, which looks brighter

around its edge). How the ring was formed was not hard to imagine.

As the fast wind expanded, it had a harder time pushing through the

thicker part of the slow wind, and piled up. You get a circle of

gas that way, and when tilted it looks like an ellipse, like

the rim of a drinking glass seen edge on.

The problem was those two outer rings. When you collide winds, it's very hard to get a thick inner ring and two outer ones. A lot of theories cropped up, some of them pretty wacky, but none really did a good job explaining how those rings formed. We still are not exactly sure, ten years later!

My role in all this was fun. As I said, I was looking for a degree topic at the time, and Roger Chevalier offered me a position analyzing Hubble data. He was part of a group called SINS, for Supernova INtensive Survey. The plan was to use Hubble to learn everything we could about supernovae, and 87a was just the first. Hubble was still a month from launch when I said yes, and I was just as downtrodden as all the other astronomers when we found out the mirror was flawed. We got two simple images of the supernova and that was it. The defocus in the mirror meant a lot of delays in projects, and ours was in that category, So from April 1990 to June 1992 all I had were those two images.

I did the best I could. I was new to this sort of thing and still learning,

and I was just figuring things out when we got new observations in 1992.

In July of 1992 I visited the

Space Telescope Science Institute

(coincidentally, a week after my first date with a woman who would later

marry me), to learn how to deal with the data.

With two sets of images paced apart by two years, we started to learn

things.

For one thing, the ring was fading! Remember, the ring existed

for 10-20 thousand years before the supernova went off. The flood of

light from the explosion lit the ring up like a flashbulb lights up a

room. The ring itself didn't generate light, so it immediately started

to fade. We were able to figure out the density of the ring from the

rate at which it faded; dense gas fades faster, low density gas fades

slower. We found the gas to have a density of about 10,000 atoms

per cubic centimeter. Sound like a lot? On Earth, our atmosphere

has about 3 quadrillion times that density! So the ring

is really a pretty good vacuum compared to gas like we have here on Earth!

For one thing, the ring was fading! Remember, the ring existed

for 10-20 thousand years before the supernova went off. The flood of

light from the explosion lit the ring up like a flashbulb lights up a

room. The ring itself didn't generate light, so it immediately started

to fade. We were able to figure out the density of the ring from the

rate at which it faded; dense gas fades faster, low density gas fades

slower. We found the gas to have a density of about 10,000 atoms

per cubic centimeter. Sound like a lot? On Earth, our atmosphere

has about 3 quadrillion times that density! So the ring

is really a pretty good vacuum compared to gas like we have here on Earth!

The ring held other surprises. By coincidence, there is a star superposed

on the ring. It's a star a bit brighter than the Sun; it's a lot like

Sirius, the brightest nighttime star in our sky. However, this

star is a lot farther away than Sirius, and thus a lot dimmer. Astronomer

Lifan Wang pointed the star out to me, and I was able to figure out

what type of star it is. I have heard people refer to it as

``Plait's star'' which I'll admit is pretty cool. In the image to the

right, the star is located on the ring in the lower right hand corner

at about 4 o'clock. It can be seen in the six image collage above as

well.

The ring held other surprises. By coincidence, there is a star superposed

on the ring. It's a star a bit brighter than the Sun; it's a lot like

Sirius, the brightest nighttime star in our sky. However, this

star is a lot farther away than Sirius, and thus a lot dimmer. Astronomer

Lifan Wang pointed the star out to me, and I was able to figure out

what type of star it is. I have heard people refer to it as

``Plait's star'' which I'll admit is pretty cool. In the image to the

right, the star is located on the ring in the lower right hand corner

at about 4 o'clock. It can be seen in the six image collage above as

well.

The images I worked with proved valuable in our understanding of the ring. It helped the SINS project, too: we had the only detailed time-based series of observations of an object that was fading away before our eyes, so it was easy to defend getting more observations. The head SINner, Bob Kirshner, was able to use that fact to make sure we got the observations we needed.

``My'' images were later superseded by ones taken with the repaired telescope, and we learned even more. Since then we've upgraded Hubble with better instruments and observed the ring over and over again. As a matter of fact, it was an observation of the ring using one of Hubble's new instruments that showed us the ring still had some surprises waiting for us... and (you guessed it) more about that next week.

Are you a glutton for punishment? Then take a look at the paper I published about all this data. It's very technical; but then, it's basically my PhD thesis!

|

|

| THE PANTRY: ARCHIVE OF BITESIZE SNACKS |

|

|

| Subscribe to the Bad Astronomy Newsletter! |

| Talk about Bad Astronomy on the BA Bulletin Board! |