| Bad Astronomy |

|

|

|

BA Blog

|

|

Q & BA

|

|

Bulletin Board

|

| Media |

|

|

|

Bitesize Astronomy

|

|

Bad Astro Store

|

|

Mad Science

|

|

Fun Stuff

|

| Site Info |

|

|

|

Links

|

| RELATED SITES |

| - Universe Today |

| - APOD |

| - The Nine Planets |

| - Mystery Investigators |

| - Slacker Astronomy |

| - Skepticality |

Buy My Stuff

Keep Bad Astronomy close to your heart, and help make me

filthy rich. Hey, it's either this or one of those really

irritating PayPal donation buttons here.

The Disc Around Beta Pictoris

Week of January 12, 1998This past week has been very interesting. Your Bad Astronomer just returned from a meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS). The meetings are held twice a year, with the January meeting usually being the larger of the two. This year was no exception, with about 2500 astronomers in attendance in Washington, DC. Usually, big news is released to the public during this meeting, and this time was no exception. One particular bit of news is the focus of this week's Snack. I apologize for the length of this snack; usually they are short, but this topic and the situation around it deserves a bit of attention. Think of this as more of a brunch. ;-)

The subject here is a relatively nearby star with the unassuming name of Beta Pictoris (commonly called "Beta Pic" for short). About 15 years ago, Beta Pic was found to be encircled by a nearly flat disk of dust, large enough to be resolved using ground based telescopes. The star was known to be young, and it is therefore thought that the disk is matter left over from the formation of the star. The big question: are planets forming in that disk? Are we witnessing the birth of a solar system, or is one perhaps already born inside there, still wrapped in the gas and dust of its birth? No one knew. The star may be close by in relative terms (it's about 60 light years away), but is still far enough away that any planets would be undetectable. Worse, the disk of dust would enshroud any newly formed planets, making them impossible to see anyway.

Then, a few years ago, a new discovery was made: the disk was warped. Like a phonograph record (remember those?) left in the sun, part of the disk was seen to "sag" a bit, while the corresponding part of the disk on the opposite side of Beta Pic was bent up. It was as if the disk was doing "The Wave". Hopes ran high, because a likely culprit to cause this was a planet, or planets, inside the disk. Gravity from a planet could affect the disk this way. The problem was, the warping of the disk was happening pretty far out, and the theories had a hard time showing a planet could make a warp at that distance.

Then STIS, the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, was placed aboard the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). Regular Snackers may remember some past tidbits about STIS. One thing it can do is take very high resolution images, in a sense zooming in on the very inner regions of the disk around Beta Pic. What did it find? The disk bulged in two places, just like the outer warps, but much closer to the star. The bulges were not much farther out than Pluto is from our own Sun (incidentally, note that I am taking pains to distinguish a "warp" from a "bulge": a warp is where the whole disk is bent, like someone took a pair of pliers to it and warped it; a bulge is simply a lump in the disk, where it appears to swell up at a particular spot).

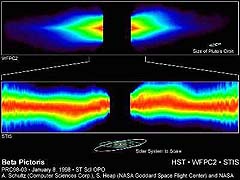

(This image is a smaller version of the image that can be found

at the

Space Telescope Science Institute's Office of Public Outreach

press release page. The top image is from WFPC2, and

the bottom from STIS.)

(This image is a smaller version of the image that can be found

at the

Space Telescope Science Institute's Office of Public Outreach

press release page. The top image is from WFPC2, and

the bottom from STIS.)

At the AAS meeting last week, the new STIS image of Beta Pic

was revealed. Dr. Sally Heap, the principle investigator of

this project using STIS, had discussed the inner bulges with

theorists. Before the new STIS images, the theorists

thought that perhaps pressure from the

intense light coming from Beta Pic itself might have caused the

outer warp, but the new observations seem to preclude that.

This means that the most likely cause is indeed a planet. Further,

Dr. Heap concluded that the planet might be as small as ten times

the mass of the Earth, or as large as seventeen times as massive

as Jupiter. It depends on the distance of the alleged planet

from Beta Pic; the farther in it is, the more massive it must be

to affect the disk farther out.

Interestingly, other new HST images may make the situation more complicated. Dr. Fred Bruhweiler, a colleague of Dr. Heap's, also has Hubble images taken of Beta Pic. His images were taken with the Wide-Field/Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2), and show the disk much farther out than the ones taken by STIS. While those images definitely show the disk is not flat, it is not clear to me immediately whether his images show a warp or if they show a bulge (just for now I'll refer to them as well as "bulges"). Either way, Dr. Bruhweiler feels that his images show that perhaps a passing star or brown dwarf (an object that is smaller than a star but bigger than a normal planet) perturbed the disk, distorting it far from Beta Pic. The outer bulges appear to line up with the inner bulging; that is, the disk bulges up on the northeast side close to Beta Pic (as seen by STIS), and also bulges up much farther out (as seen by WFPC2) in the same direction.

It is uncertain if a passing star could cause the inner bulging, or if a massive planet orbiting Beta Pic could cause the outer bulges. Perhaps one cause led to both effects. Perhaps the inner and outer bulges were caused by two totally different effects (essentially making both astronomers correct), and they coincidentally line up as seen from Earth. Currently, Drs. Heap and Bruhweiler disagree about the details of the cause. This disagreement is the very core of science; it virtually guarantees follow-up observations will be made. Once taken, they will be examined, and the theories tested to see which best explains the observations.

In the meantime, this disagreement, and the observations themselves, have caused a minor media frenzy. Therein lies some Bad Astronomy by the media, but that is another tale to tell. Stay tuned!

|

|

| THE PANTRY: ARCHIVE OF BITESIZE SNACKS |

|

|

| Subscribe to the Bad Astronomy Newsletter! |

| Talk about Bad Astronomy on the BA Bulletin Board! |